History & Geology

Free / History & Geology

The Birimian Greenstone Belts of West Africa

June 2013 by Chris

A few years ago I had a tremendous opportunity to visit Australia and hunt for gold there. The geology of the gold deposits there was somewhat different from what I was used to here in the US. I learned a lot about greenstone belt gold deposits while prospecting them in person, and it was an amazing trip. I heartily recommend Australia to any prospectors who have the money and the desire to visit.

Recently I was offered something very different—an unusual opportunity to join a group of people visiting West Africa and the greenstone belt gold deposits there. This area has become the target for gold exploration by many mining companies, and a tremendous number of new finds have been made in recent years. The gold deposits of this area are not well known, so let’s take a closer look.

There is no place on this planet that has not been explored at least to some extent for gold, but there are places that have been looked at only in a cursory way. Because of political unrest, poor access, easier and better prospects elsewhere, and a whole lot of other reasons, exploration in much of the West Africa area has never been done before with modern technology and geologic tools. Things have changed somewhat in recent years as some (not all) of the countries in this area have recognized that they can benefit from orderly development of their natural resources. These countries have rewritten their mining laws to modern standards and set requirements for ownership such that the mining companies can make a good profit and local citizens get good paying jobs. Meanwhile, the government can generate income as well. The result is that many gold mining companies are sitting up and taking a real interest in this area.

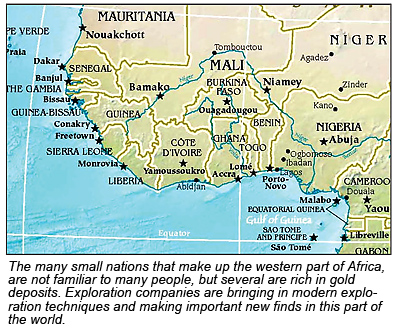

The goldfields of western Africa are spread across a number of different countries, so many different small nations are involved in this new gold rush. There are parts of 17 nations touching the goldfields in this area. They include Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Ghana, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Liberia, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo. Many of these nations are little known to our readers, but each has their own laws and culture. All the different governments can be daunting for mining companies to deal with, but companies are coming to this area because there are large and undiscovered bodies of gold ore here.

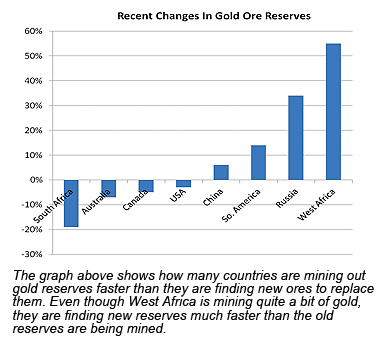

The potential of each country for gold finds also varies considerably. Some of them have already become important world producers of gold. While South Africa remains the country that produces the most gold on the continent of Africa, the second most productive is Ghana, third most productive is Mali, and fourth most productive is Burkina Faso. All are in this West African greenstone belt area. Ghana, Mali and Burkina Faso  together are now producing a total of about 6.7 million ounces of gold per year. In the last few years, the known gold resources of the US have actually gone down as we mine out more than we discover, but in western Africa, the known amount of gold ore in the ground has increased nearly 60%.

together are now producing a total of about 6.7 million ounces of gold per year. In the last few years, the known gold resources of the US have actually gone down as we mine out more than we discover, but in western Africa, the known amount of gold ore in the ground has increased nearly 60%.

Last year I wrote about how small-scale, artisanal miners are rocking the world of gold production, and this is a part of the world where millions of individual miners are actively working. I expect to see some of this myself while I am there. These countries are among the poorest in the world and the lure of making a few dollars a day digging for gold with hand tools has attracted a huge number of people who work the deposits on the surface by their own muscle power, manually crushing the weathered rock and extracting the gold with gold pans and mercury. Many governments are concerned about mercury use, as the miners often handle it in an unsafe manner. Mining companies sometimes have serious difficulties when small-scale miners invade their properties and work the richest parts of the surface deposits. This problem varies quite a bit from country to country. Small-scale artisanal mining is a brutal life, but the local residents are amazingly poor. Gold mining has fed millions and brought an influx of money and benefits to countries that are destitute.

In addition to the fine-sized, hard rock gold the individual miners work, there are also nuggets. Some operators are using metal detectors to find them in a way similar to the big gold rush that occurred in Sudan a few years back. Nuggets here are not as large and the publicity is not as great as Sudan, but the geology is similar and some good gold is being found in this part of the world. The advantage of metal detectors is that they release no mercury into the environment, but the disadvantage is that they cost so much more than the typical resident can afford. Some of these small miners are also starting to discover the potential of dry washing rich placers to recover fines not normally seen by a detector.

As noted above, a lot of mining companies, from smaller exploration outfits up to the larger big time operators, are setting up for work here. Commercial exploration often makes use of the exploration of the native miners who dig and test the ground extensively in their search for paying deposits. Drilling of the areas found by the small operators to search for deeper extensions of the surface deposits has led to a number of valuable finds—even deposits containing multiple millions of ounces of minable gold.

It does seem humorous to me that the geologists in their search for ore are out chasing the gold rush to see what the artisanal miners have located. In part, this is due to the fact that only limited information on the geology and deposits of these countries is available. Exploration is complicated by poor rock exposures due to deep weathering and poor access roads. Most mining companies need to send out their own staff and generate their own information before they can even get started.

Geophysical methods, including magnetic and electromagnetic surveys, have been helpful in delineating rock types and contacts. Because of the lack of existing information, the geologists are making use of whatever information they can get their hands on, and this includes the success of individual miners who are working in the area.

Geology

Africa actually has a number of productive greenstone gold belts, but the Birimian Belts of West Africa are the best known and most productive on the continent. These types of deposits form from the collision of tectonic plates. The heat and pressure of the collision of these plates upon volcanic rocks—often ocean floor basalts—creates the hot, gold-bearing fluids that form the deposits. The main goldfields being explored in western Africa lie within the Proterozoic rocks of the Man Shield, which is part of the West African Craton, a body of very old rocks composed of granitic gneisses and greenstone belts.The most productive gold-bearing zone in this area to date has been the Ashanti Belt in Ghana, which has produced gold for centuries and been actively mined by European operators since the 1800s. Here gold is

associated in the margins of belts of metamorphosed volcanic rocks commonly referred to as greenstone. Almost without exception, the major gold deposits of Ghana and the rest of West Africa lie at or close to the contact margins of these greenstone belts where they meet up with other rocks like schist, and these structural contacts are often strongly deformed and associated with shearing forces. These greenstone belts are associated with zones of extensive shearing and faulting expressed by parallel, steeply dipping, deep fault systems, which are developed at the contact between the meta-volcanic and meta-sedimentary rocks (schist, slate and similar materials).

associated in the margins of belts of metamorphosed volcanic rocks commonly referred to as greenstone. Almost without exception, the major gold deposits of Ghana and the rest of West Africa lie at or close to the contact margins of these greenstone belts where they meet up with other rocks like schist, and these structural contacts are often strongly deformed and associated with shearing forces. These greenstone belts are associated with zones of extensive shearing and faulting expressed by parallel, steeply dipping, deep fault systems, which are developed at the contact between the meta-volcanic and meta-sedimentary rocks (schist, slate and similar materials).Gold mineralization is also associated with sheeted quartz vein swarms and stockwork zones found within granitic intrusions. These small- to medium-sized granitic intrusions are present within the greenstone belts. Because the mineralized contact zones continue on for long lengths, the gold deposits continue to trend periodically along the contact quite a distance. Mineralized zones can even continue across country borders as the minerals are not limited by lines on a map.

Because of its great age, the area has generally been worn down by the long effect of weathering and is fairly flat. While some parts are heavily vegetated, the majority of the gold-bearing areas are fairly arid and desert-like. A majority of these goldfields are located in what would be considered dry savannah or desert regions. The area is dry because it is situated along the southern margin of the great Sahara desert, one of the driest locations on Earth.

The West African craton goldfields have quite a bit in common with the ones I explored in West Australia. They are both of great age and caused by the same types of geologic forces. Both are important gold producers. Perhaps the biggest difference is the presence of large bodies of ironstone in Australia, which are not present in West Africa. In Australia, ironstone is present nearly everywhere in the gold-bearing areas I visited. In West Africa, bodies of manganese and iron-rich rock are found in place of the ironstone. I don’t know if these rocks will be noisy and difficult to work with a metal detector. The ironstone certainly was a problem, but manganese is usually not nearly as bad. I will be finding out soon!

While I stated that the amount of political unrest is diminishing in this region, there have been recent civil wars in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. Mali was recently invaded by French armed forces to control terrorists in the northern part of the country. In addition, there have also been some other cases of regional upheavals and political protests. So, while things are greatly improved, the area is not completely stable. While some countries are safe enough that they are regularly visited by tourists, others are not so safe.

I know a number of readers will be wondering about the potential opportunities for individual prospectors to hunt gold in this part of the world. I wish I could say that West Africa is an easy region to visit, but as far as I know, there are no tours or invitations to prospectors coming from the outside. Big mining companies get special invites from the government. Getting around is not easy. Not every town has a store for supplies and fuel. The roads connecting up the countryside are dirt, not asphalt. Diseases like malaria, yellow fever and even polio are common here. There are very real dangers out in the goldfields and sometimes people without assets will resent outsiders coming in to take their gold.

The group I am going with represents a special opportunity, and I am not going in just as a tourist out hunting for gold. Even so, while a part of me is very strongly looking forward to an amazing adventure, the other part of my brain is telling me that I am crazy for even attempting this. There are also language barriers to be overcome, as French is the primary language for most of the countries in this area. A couple of them are English speaking, but out in the goldfields even English and French are not sufficient—many people speak only the local tribal languages.

I had wished my trip to Australia was perhaps 15 years earlier when so many of the nugget patches had yet to be found. This trip to West Africa is in some ways the fulfillment of that—a raw and mostly unexplored part of the world.

As I write this I am only a few days from my departure. When I get back, I will share my photos and experiences. So although you may not be able to travel to western Africa, you can still get a flavor of what I hope will be a very unique prospecting adventure.

© ICMJ's Prospecting and Mining Journal, CMJ Inc.