History & Geology

Free / History & Geology

One Question, Forever Unanswered—Did He Really Find the Gold?

May 2011 by R. V.

When Boyd Spies told Louie Larson about all the gold Hogan Munson had found, Bobby Larson, as I was called in those early days, paid close attention. At this young age of seventeen I had full blown gold fever and no chance for recovery. I hung on every word.

This was one of those stories where you have no doubt that the person telling it believes it to be true. But was it? This was placer gold, and very little has ever been found in our county. To add to the difficulty of getting our facts together, Munson had taken his gold with him and gone back to his home country of Sweden. One thing my dad suspected at the time, and I now know for sure, is that Boyd Spies did have his facts straight.

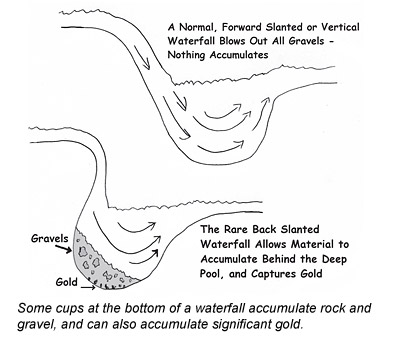

He told of a waterfall that dropped for twenty or thirty feet into a large deep pool. From this pool the stream overflowed, creating a second waterfall. Spies explained how Munson reasoned that there would be a lot of gold in this deep pool that he referred to as a “kettle.” Spies went on to tell how Munson had built a flume of logs, supported from below the falls, to carry the water over and downstream from his kettle. Once the flume was completed Munson had tunneled into his kettle from below and took out sixty thousand dollars worth of gold. This was a lot of gold and a lot of money, as this took place in 1932. It was twenty-one years later that my dad and I heard the story, and had been told the approximate location of the stream on which the gold had been found.

And so, did we find the place, and was everything as had been described by Boyd Spies? The answer is yes, but before I take you on that journey let’s fast forward fifty-five years to a picture on page eleven of the January 2009 edition of ICMJ’s Prospecting and Mining Journal. The picture is in an article titled, “Reading A River: Finding the Paystreaks—Part II,” by Chris Ralph. When I looked at that picture of the pothole in the bedrock my mind raced back in time to the “kettle” that Hogan Munson found.

Let’s go back now to 1953, and see if I can help you experience what was one of my greatest adventures.

“What do you think, Bobby?” my dad asked. “Shall we go and have a look at it?” That was one of the things I admired about my dad. He didn’t ask if I wanted to help him look for it or have any doubt about whether or not we could find this place. He said, “Shall we go have a look at it?” The only person I have ever known who was more optimistic than him is perhaps me.

We bought maps that would serve to get us as close to our desired destination as possible in a 1940s vintage pick-up truck. In those days there were many logging roads in the mountains that were shown on our map. Something else we had in those days were section markers. These were wooden four-by-four posts three or four feet high with a metal grid of the township on the back side. There was a nail placed between the section you were leaving or entering so you would know where you were. Our plan was to reach the stream at the highest elevation that was practical from the existing roads and work our way downstream in our search for the kettle and flume. How many day s of searching it would take and how difficult it would be to get there were questions yet to be answered. We followed the logging road, knowing from the map that it would not take us to the stream. It was obvious that a fair amount of hiking and compass work would be needed. We came to a point at the top of a hill where there was a turnaround. This did not seem like a good jumping off place. We remembered seeing what looked like an overgrown old road a mile or so back so we went to check it out.

s of searching it would take and how difficult it would be to get there were questions yet to be answered. We followed the logging road, knowing from the map that it would not take us to the stream. It was obvious that a fair amount of hiking and compass work would be needed. We came to a point at the top of a hill where there was a turnaround. This did not seem like a good jumping off place. We remembered seeing what looked like an overgrown old road a mile or so back so we went to check it out.

Things were shaping up nicely. This overgrown road turned out to be part of the early rail line that was used to log much of this area in the early days—the teens and twenties. We were certain we were on the old rail line when we came to a trestle over a deep canyon—one of two we would cross that day. These trestles were magnificent marvels of engineering and many were still standing. On the ones we were crossing the rails had been taken up and replaced with planks so they became bridges that were used by logging trucks. There was danger in crossing these trestles as there were spikes to trip over and planks that were rotten. You had to make sure you were always over a stringer and didn’t trip over anything. It was a long way down to the bottom of these canyons. After an easy walk of about a half an hour we came to a water course that had to be the stream we were looking for.

Now the excursion became serious. This was what we were looking for—our starting point. There was little chance that the waterfall, kettle and flume could be upstream from here. From this point there was about nine miles that this stream traveled before it crossed another road. That next road was the paved county road that was at the base of the mountain. Our plan was to search downstream as much as we could, leaving time to get back to the truck before dark. I guess I should have said safely search and safely get back to the truck. The only thing that I can imagine that could take the joy out of prospecting would be someone getting hurt.

As soon as we left the old rail grade that day we were in the thick of it. Downed trees to trip over, everything wet and slippery, and for added challenge, devils clubs.

A devils club is a beautiful plant from a distance, with long graceful stems and large flat leaves. The problem is that these graceful stems and beautiful leaves are covered with the worst stickers that you can imagine, and they always grow where you need to be. And so it was as we fought our way downstream. Fortunately we didn’t have far to go. The first clue that we were getting close was an old building made of poles and hand-split cedar shakes. Next we found what looked like a wooden walkway built beside the stream. Then we saw that we were approaching a deep canyon. This was it. There was the trough made of logs and the stream disappeared from sight. It was all there and still standing.

At that point in my life this was the most dangerous place I had ever been. We could see where the creek disappeared and could hear the waterfall—we just didn’t dare to get close enough to the edge to see it. We were at the top of a small box canyon.

Our only way to see the waterfall and kettle was to skirt along the hillside until we could find a way into the canyon, and then come back upstream. It was not easy and could not have been accomplished without tying a rope to a tree to help us down the last twenty feet or so. We looked at the tunnel that had been driven into the bottom of the kettle through which the gold had been taken out. The waterfall splashed at the bottom of the kettle and ran out through the tunnel. Looking up we could see that there was a distance of about three feet betw een the flume and the waterfall. Whatever had connected the two was missing or the flume had shifted away from the mountainside. I wonder how Munson had connected the stream to the flume. When I considered that flume, or trough of logs, or whatever you want to call it, I get the feeling Hogan Munson could have accomplished anything he set his mind too.

een the flume and the waterfall. Whatever had connected the two was missing or the flume had shifted away from the mountainside. I wonder how Munson had connected the stream to the flume. When I considered that flume, or trough of logs, or whatever you want to call it, I get the feeling Hogan Munson could have accomplished anything he set his mind too.

It was all as Boyd Spies had said. Only one question remains that will forever be unanswered: Did Hogan Munson actually take sixty thousand in gold from the kettle? I certainly hope, and do believe, that he did. I also believe that I will be able to find the source of the gold the stream carried to the kettle.

Now I will answer as many of your questions as possible. I know what they are. Questions like: Did I find gold at this location? If not, why not? It’s been fifty-eight years, what’s the holdup? Where is this place? Okay, okay, okay. I’ll try to make some sense as to why it has taken so long. The only thing I can’t tell you at this time is the location, as this is my number two project for this year.

I was young and very inexperienced at that time and didn’t have a grasp on just how important it was to find out where the gold in the kettle had come from. Not long after this first experience, a bridge on the lower portion of the logging road washed out leaving a two and a half mile hike to the place we had previously parked the truck. Two years slipped by before I mentioned this gold creek to my girlfriend’s father. He thought it would be worth the effort to have a look. We didn’t find any gold. We might have except for the fact that he found a hundred and ten pound jasper agate.

This man, Roy, had some knowledge about rocks, and all thoughts of finding gold were replaced with how we were going to get this boulder home with us. He thought it was worth a fortune. The rock barely slid into my packsack. We hoisted the pack up on a stump or other opportune high spot many times as we took turns packing it out. One of us would balance the pack while the other got the straps over his shoulders and stood up. Picture a pack animal staggering from side to side as he adjusted to the weight of this terrible load, and off we went. The straps on the pack held, but the wooden frame broke right away. It was necessary to place our jackets between the pack and the person carrying this awful thing as it would just dig right into your back. It was worth it though—we were bringing home a treasure. When it was time to trade off on pack duty, the one carrying would lean the pack against the bank on the uphill side of the road. The other one would keep the pack from sliding downhill while we traded jobs. Such a grand feeling it was when we finally reached the car.

My friend had a diamond saw, but one made for an average rockhound. Roy knew of a man in Lynden, a town twenty miles north of us, who had a very large diamond saw. The plan was to get this man to cut the rock into small enough pieces for Roy’s saw to handle. We were sure this person would be happy to do this for a small share of our prize.

We found the man with the saw, and he was willing to have a go at it. It seemed to take forever to cut through this huge rock, but perhaps that was better than being disappointed right away. Once it was cut and cleaned we wet it so we could see what we had. I didn’t know what inclusions were at that time, but I could read the concern in their voices when they expressed how many inclusions there were. I did know what fractures were, however, and when I heard the words “thousands of fractures” I knew the value of our treasure had diminished.

When you expend so much effort in bringing a worthless rock home you do need to find a use for it. Roy’s wife had a flower garden beside their house. Roy broke the jasper agate into softball-size chunks and made a border around the flower bed. Now, fifty six years later, when I pass by their old house on my way to town, I get to see the flower garden with a border of jasper agates.

The next year I went on active duty in the Navy. Once my military obligation was out of the way I found work and decided it was time to get married and raise a family. I found a good wife on my second try and we raised four kids. Prospecting was always on my mind, and I got away occasionally, but for most of the time my nose was to the grindstone.

It was many years before I again returned to the Hogan Munson prospect. In the early 1970s, I decided to have another look. The first thing I learned was that the old logging road that took us as far as the washed out bridge could no longer be used. Houses had been built on the lower portion of the mountain and the road was now private. On my maps I found other logging roads in these mountains that might serve my need. One road, north of the prospect, was a distance of only a mile and a half, but a mile and a half can be a long way in the dense growth of brush and timber we have here in the Pacific Northwest. I calculated a compass bearing and planned my trip.

In my younger years, planning a trip meant being on my way the first opportunity to get enough time off work. On most of my early prospecting trips I went alone. I would leave a map with my wife showing where I would park my rig and my destination. So many times I heard her ask, “When should I start to worry?” Somehow I always made it back before panic set in or a search party assembled. In those days fear was pretty much unknown and bravado would sometimes take the place of sound judgment. I look back and shake my head when I think of all I did, alone in the mountains.

I followed a compass course and came out exactly where I wanted to be. However, it was a difficult trek, and with gold at $35.00 an ounce I lost interest.

In the early 1990s, I was working as a real estate agent and sold a house to a prospector. We were soon partners, and he and his wife wanted to see the Munson prospect. We obtained permission to use the private road and were able to hike in the easy way, up the old logging road from the washed out bridge. What a difference forty years makes. The old road had grown up trees, but was still possible to follow. The two railroad trestles had fallen into the canyons, making the trip much more difficult. We found our way into the old Munson workings. The flume was no longer standing, but I was able to show my new partners the kettle with the tunnel into it. We were able to pan some color from the stream, but very little. My partners knew of better prospects, some you could drive to.

Fast forward another eighteen years to 2011 and we find the price of gold at nearly $1,500 an ounce and realize that many old prospects are worth another look. The Munson prospect will get another look this year, as soon as the snow is off. I’ll let you know how it goes.

© ICMJ's Prospecting and Mining Journal, CMJ Inc.