Prospecting & Detecting

Free / Prospecting & Detecting

Mud Men: Pocket Miners of Southwest Oregon—Part I

February 2011 by Tom

Was the motorcyclist suddenly swallowed up by a time warp—maybe a worm hole—or was this just another “normal” event? The strange situation started when a motorcyclist in a remote forested area was exploring the numerous trails and roads. Out of curiosity he slipped off his off-road machine and pushed it around a sturdy locked “government gate” blocking a side road. Several times before he had sneaked into this area blocked to normal traffic, but this time he decided to take a narrow, little used spur trail just wide enough to fit a Jeep. A short run with a few winding turns brought him uphill to a level spot. Even before this explorer had reached the end of the trail he knew he was at a very strange place and apparently in deep trouble. He stopped the machine and rested on one foot, afraid to go forward or even to beat a full throttle retreat.

His hasty glance showed him that there was human activity in the clearing. Smoke rose from some sort of fire pit originating from an object that could have been some type of cooking pot. A careful look around was impossible because his attention was focused on the strange looking figure in front of the smoke. He was big, bearded, and very wild looking, covered head to foot in some sort of reddish body paint. In primitive tribal fashion this “native” was totally naked and looked very unhappy to be disturbed during what could have been the performance of some sort of ancient ritual. Further showing that this motorcyclist was not welcome, the primitive looking man was holding a weapon pointed at the ground in front of this intruder. The weapon was motioned in a “come over here closer, don’t leave right now” manner.

Our motorcyclist certainly was wishing he could leave right then and motor away pronto on any number of other roads, but recognized the danger in bolting and trying to escape. The distance between the two was 70 or 80 feet and getting close to the effective range of primitive weapons such as arrows and blow guns. However, the weapon being brandished by the naked warrior was a stainless 1911 model Colt automatic pistol. While it is true that this warrior had fought in jungles battles, it was in Viet Nam during the 1960s. Yes, the answer to the above puzzling circumstance is simple and understandable when more background information is revealed. This motorcyclist had merely wandered onto an active mining claim belonging to a hard working gold pocket hunter processing dried clay-type ore through a small impact mill at a location west of Jacksonville, Oregon near the Applegate River.

When more facts are known, the incident seems less bazaar. The miner, despite his “primitive man” appearance, turned out to be a well educated retired professional. He elected to strip down so he could wash the material off his unclothed body easily with a water bucket when milling was completed so he wouldn’t track mud into his 2007 SUV and hence back home.

Despite the difficult circumstances when first contacting each other, the miner (who grabbed a towel out of politeness) and the intruding motorcyclist eventually had a constructive conversation discussing various roads and trail connections and left the clearing on reasonable terms. The biker, however, has never been seen in that area again.

What are gold bearing mud and clay deposits? The type of ore in this particular type of deposit is know as “gold bearing mud” or “clay seams” (also known as “puddin’ rock seams”) and have been observed in many mining regions of southwest Oregon and elsewhere. Such deposits are little understood and are scarcely mentioned in official geologic literature. They are seldom recognized today for their importance.

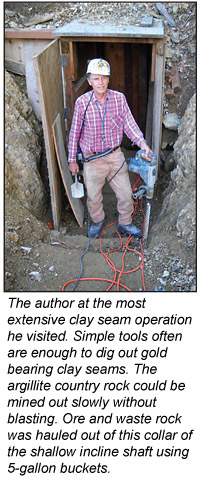

Their potential value stems from a surface indicator of buried lode deposits nearby as well as a source of rich, small pockets of gold ore. Since they are generally on or near the surface and often quite rich they can be worked in many instances just using pick and shovel. Another reason these long overlooked deposits are now attracting more interest during this period of high gold prices is the ability to extract the gold from these ores using relatively inexpensive and portable equipment. Just a few “mud miners,” as they are sometimes called, seem to have a usable understanding of the deposits and the potential gold riches therein.

Their potential value stems from a surface indicator of buried lode deposits nearby as well as a source of rich, small pockets of gold ore. Since they are generally on or near the surface and often quite rich they can be worked in many instances just using pick and shovel. Another reason these long overlooked deposits are now attracting more interest during this period of high gold prices is the ability to extract the gold from these ores using relatively inexpensive and portable equipment. Just a few “mud miners,” as they are sometimes called, seem to have a usable understanding of the deposits and the potential gold riches therein.

In preparation for this article it was noted that many sources and individuals interviewed seemed to use the terms “clay” and “mud” somewhat interchangeably. Mud can occur when most forms of soil have a very high moisture content and the product becomes slippery and gooey. Clay denotes a product of weathering and oxidation or mechanical action that leaves very small-sized particles that have a loose molecular bond that helps them stick or cling together.

The term clay does not mean a specific chemical content, but denotes its character—very small particles of mineral that when wet have considerable stickiness and mold ability. Common clays are often hydrous aluminum silicates with various additional ingredients and often have the quality of vitrification such that they can be fired in a furnace and become brick-like.

Disclaimer: Over time, as more understanding of these deposits comes to light, additional information will be shared by prospectors and miners developing a mud/clay seam occurrence model as discoveries and development continues.

So far we have come up with a few generalizations regarding goldbearing mud/clay seams. First, only certain clay seams carry gold. With some, a little study of the site of gold-yielding clay gives a geologic explanation as to probable cause and source of gold mineralization. For example, many gold deposits in southwest Oregon are found in metamorphic and sedimentary rocks close to intrusive zones where granite or similar igneous rock has pushed up to the surface. These gold-bearing clay seams form from the in-place decomposition of gold ores. They may occur along bedding planes or within boundaries of fissures and/or faults. These structural features facilitate a “plumbing environment” wherein some gravity, chemical or mechanical transport may occur.

Clay seams are not to be confused with eluvial or alluvial placer deposits. Eluvial deposits form “pseudo placers” in the soil from weathering or decomposition of gold ores or other primary sources and are built-up layers on or very near the bedrock surface. Gravity action, over eons of time, moves the released gold particles downhill.

Alluvial placer deposits occur when eluvial deposits are moved by water action and subsequently concentrated or redistributed in various places downstream. The clay layers in alluvial placer deposits are generally originated from certain low energy stream flow conditions where fine-sized particles accumulate from transport. Alluvial layers of clay with entrapped gold can also be extracted using the methods described in this report.

In contrast, “gold-bearing clay seams” in this article refers to gold more or less in place where it has been liberated from host rocks/ores by weathering, chemical and mechanical means. These host rocks may be volcanic, metamorphic, sedimentary or a combination of these. The gold-bearing clay seam thus occurs within a “plumbing environment” that conveys hot, mineral-laden solutions outward into the host rocks from intrusive felsic igneous rocks with generally a higher level of quartz such as granite.

Usually gold-bearing clay seams can be prospected for in the vicinity of established gold mining areas, mineralized zones, known gold veins, shear zones, faults, contacts of certain metamorphic and sedimentary rock zones, and especially at the edges of intrusive igneous rocks such as granite in the form of batholiths, dikes, or laccoliths. Of course, most gold deposits have one or more of these characteristics.

Rocks and minerals associated with clay seam gold deposits in southern Oregon are often in sedimentary rock units at least partially metamorphosed into argillite. They are also associated with mafic volcanic rocks, basalts and gabbro that are metamorphosed into greenstone.

Greenstones are rocks containing sodium-rich plagioclase feldspars, with chlorite, epidote, and quartz formed from ancient sea floor material that is metamorphosed as it is squeezed between tectonic plates. The grain size is usually small. Often where these rocks are close to the contact with serpentine is a likely zone for gold mineralization.

Serpentine is a hydrous magnesium silicate, often containing iron, chrome and nickel. It is formed from the alteration of intrusive rocks like dunite and peridotite from the upper mantle that are intruded up along very deep seated faults.

Usually the clay seams are shallow, in the oxidation zone where the topography has allowed very slow weathering in place. Expect depths to be from 5 feet to 30 feet. Also, they are commonly very small in strike, as exposed on the surface with lengths from 5’ to 50’. They can be found individually, but also in swarms that when close enough can be worked in open pit fashion.

The clay seam values may be concentrated in zones 0.2 inches (5 mm) to 2 inches (50 mm) wide. Interestingly, unlike laterite soils and saprolite, oxidation zones may be very narrow in width across the strike with unoxidized country rocks on either side. When sinking an exploration pit or shaft on these seams, sometimes a miner may see a change within a relatively short depth out of the oxidized zone where the clay changes character to much more like a vein with calcite minerals. Limonite, a common mineral in oxidized zones, is a chemical breakdown of iron-based minerals.

Laterite soils are reddish residual soils found in many areas of southwest Oregon and south into California’s Klamath Mountains. The red coloring is the result of hot humid climate and poor drainage (at least in prehistoric time) that allows the feldspar and even the quartz to leach away, leaving iron oxides, iron hydroxides and aluminum hydroxides that often are clay like. Gold is often concentrated in such laterite soil. There can be zones of gold-enriched clay soil where a gold vein has been largely removed by the leaching from a depth of a few feet to hundreds of feet in tropical areas. However, as with saprolite, the oxidation is spread out rather evenly over a whole area.

Saprolite (or “rotten rock”) could be considered the first stage of formation of a laterite soil. The leaching process has just begun to remove minerals such as feldspar leaving the quartz behind. Saprolitic rocks are characterized by looking like the original rocks but easily falling apart.

Expect the clay seams to vary extensively in gold content. Many seams have extremely small particles of gold that can just be seen with 10x magnifier when panned out, while other locations in this general area may yield rope like gold wires. One gold wire found recently was 25 mm long and 3 mm in diameter. After bouncing around in a bottle filled with water, small colors of gold were seen just falling off the main body of the specimen. It is theorized that some of the larger gold particles (including the one mentioned above) are agglomerations of smaller gold particles. As observed in unoxidized auriferous pyrite ore with minute gold particles in the pyrite crystals there is a change of size of gold particle in the oxidized gossan or iron hat of the same deposit. Here some of the particles of gold liberated from the sulfides have formed together in larger particles or even nuggets.

On some clay seams examined, “sugary quartz” was found when washing out the clay. The rough looking quartz showed crystal faces. It is theorized that the mud zone was rich with calcite mineral containing some crystals of quartz as well as auriferous pyrite and other sulfides. As this material oxidized near the surface, watery solutions became increasingly acidic from decomposition of sulfides into weak sulfuric acid. It dissolved much of the calcite mineral leaving the quartz, with gold freed from the sulfides and sludge from the calcite rich minerals as muddy sludge or iron-rich clay.

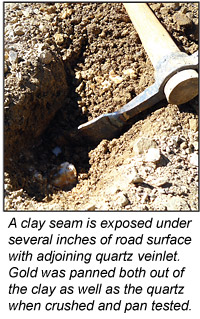

Bordering country rocks showed little weathering, but lens of quartz (some with little pyrites or sulfides) were observed adjacent to gold-bearing clay seams. Gold-bearing mud seams can be distinguished from surrounding soil and rock by variations in color. A common color is brick red. However, some with manganese were very black or showed streaks of manganese minerals. Frequently the gold is stained or coated with iron oxide minerals (red to black) or manganese (black). Certain detectors can identify a seam from the country rock when ground balanced first on the country rock. One “mud miner” stated, “You have to train your eye not just to look for the color of quartz.”

The seams can be found in more or less vertical strikes similar to quartz veins and are considered a form of lode deposits. Often they are observed skirting the edge of other structures. At times the clay seams are quite close to the surface (five feet, for example); however, when the source of the clay is highly associated with the grinding movements in a fault or shear zone the clay layer may be much deeper.

On surface exposures downhill from outcrops of gold-bearing zones, gold-bearing clay can be found in flat layers below the soil cover and above the less oxidized country rock. These eluvial deposits are the result of residual build up of the less soluble minerals and are often very shallow, just inches thick to a dozen feet or more. As the parent rock weathers or dissolves away only the gold—and to a degree even the iron and clay minerals—is left behind. When transported to a stream by water, the gold and clay mineral could contribute to alluvial stream deposits.

Recovering gold from the mud material can be difficult, but a reasonable recovery can be made by relatively simple and portable equipment. In some locations most or all of the gold is in the clay, but in others the adjoining rock or quartz may have to be pulverized to recover the gold. Quick panning techniques that often work well for some crushed and milled lode samples may not reveal much gold from some of the clay samples. Special pre-washing and panning techniques may be required.

When the material is thoroughly dry it can be milled in impact mills and then washed through a concentrating table. Another method for small batches is boiling and then panning—when the small water molecules expand into steam, the molecular bond of the clay is disrupted. Chemicals can be used to help break the molecular bond but may not be environmentally friendly.

—to be continued next month...

© ICMJ's Prospecting and Mining Journal, CMJ Inc.