History & Geology

Free / History & Geology

Know Your District

December 2010 by Michael

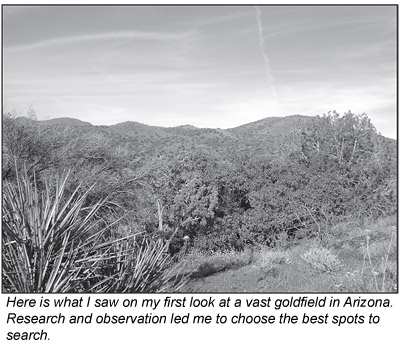

After driving for hours with an uncontainable excitement about what you might find in a new gold district, you step out of the car and look out on what seems like an endless horizon. Once you are on the ground, where exactly do you start your search for that elusive yellow metal? Unfortunately, gold doesn’t always follow the rules and what you’ve found to be true in other districts might not apply here. Some common traits among successful prospectors are quality research, knowing what signs to look for, and an ability to always be learning out in the field.

Before you ever take a trip into the gold fields you’ve hopefully started out by doing research on the area you want to prospect. This can save you from much fruitless effort. For instance, if you are a metal detectorist, you would want to be sure your area is a producer of coarse, nuggety gold. There are many fabulously rich gold districts that have only produced fine gold, with nuggets being extremely rare. If you set out detecting in one of these districts you can find yourself trying to squeeze blood out of a turnip. On the other hand, you might have great success there if you’re using a sluice box or a drywasher.

Some of the best sources of information are old government reports and bulletins that were issued by state mineralogists, the USGS and the now defunct US Bureau of Mines. Since these documents have no copyright protection, you can find  many of them on the Internet. These reports and bulletins contain information on many gold districts, often including what the old timers were finding, the types of rocks present and specific locations where gold and other precious metals were found. You can combine this with information contained in more recent books and magazines to give yourself leads in a particular district.

many of them on the Internet. These reports and bulletins contain information on many gold districts, often including what the old timers were finding, the types of rocks present and specific locations where gold and other precious metals were found. You can combine this with information contained in more recent books and magazines to give yourself leads in a particular district.

Don’t ignore geologic maps in your research. If you can find geologic maps on an area of interest you may be able to locate a commonality between where mines and workings are located and where certain geologic features are found. It can be quite obvious when looking at hard rock mines sometimes. You may see that at certain contact points between features there will be mines situated all along it. With old tertiary channels in California’s Motherlode, andesite capped these old rivers. Those rich river gravels were often worked by drift mining under the andesite cap. You may see a couple of these drift mines at the edge of the caps and could reasonably presume that river gravels bled out from under the cap to enrich the drainages around where those drift mines show up on the maps. With this research you’ve not only learned which districts would be suited to your needs, you’ve also begun to learn about some of the specific items you should be looking for in the district.

While gold is usually associated with things such as schist, greenstones and quartz, these are by no means the exclusive indicators of gold. If you were looking for these signs in some of the districts where I’ve had my best success you would never be successful. Even in districts of seemingly typical gold geology, you will find areas that will produce better gold than others. This is where the ability to continually learn from your experiences will help fill your poke.

I have found no better source for learning a new area than those who have found gold there before me. And while many prospectors can be quite tight lipped about what they’ve learned or where they’ve found gold, those who have passed on readily give up their knowledge if you’re willing to look and learn. We have to remember that the earliest miners were not geologists, but came from a variety of backgrounds. Their survival depended on finding enough gold so they worked hard and adapted to whatever challenges these new areas presented. Through their trial and error, persistence and extremely hard work they left clues we should be looking for.

“Why did they look here?” is one of the first things many new prospectors say when they see old workings. In your eyes that spot may look the same as all the surrounding area. When you find these old workings look for which rocks and minerals are present. Take notice of everything from the terrain to the material they were working. Make a note of similarities with other nearby workings. Does this one have the same rocks present as the last one and are they not found in most places in the area? If you’ve noticed a similarity you may have just found a good indicator.

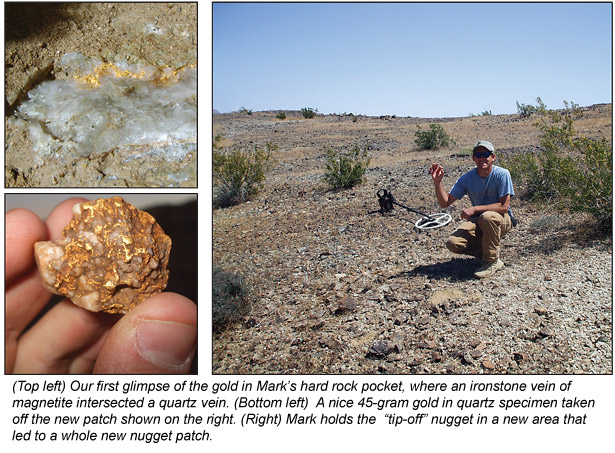

One district where I have had great success has little or no schist, is primarily granitic, and has an abundance of quartz. While this basic geology covers many square miles—most of it barren—there are unique indicators I have found that cause me to immediately fire up my detector. In observing where the old timers worked I noticed that magnetite was always present in the old placer workings. The many gullies in the area are void of magnetite and the old miners avoided them. As a result, I work areas where I find magnetite, whether the old timers worked them or not, and this method has produced many quality nuggets.

In this same district, my brother and prospecting partner Mark made these same observations and used these facts with great success in detecting gold. In one location he recovered many good gold-quartz specimens based on previous observations of old prospects and pocket locations. It was right where a vein of magnetite intersected a quartz vein.

The old timers likely didn’t know the gold dropped out of solution at this spot but they definitely picked up on the fact that gold was associated with magnetite. My point is: You don’t have to be an expert in geology to have success, but your success will come more often with observations like these.

At another location, I found the geology looked very different from any place I had ever searched but there were a number of what appeared to be pocket mines in the area. The one thing I had observed was that at every hole the old timers dug there appeared to have calcite in small amounts. This led me to search an area where I quickly pulled out several half-ounce nuggets with a unique character to them—attached to all of them were small amounts of calcite. Later, not but a few feet away, a specimen in calcite was found that contained seven ounces of gold.

It can be daunting finding that first piece of gold in a new area. In this modern day of technology and information, you can help your cause greatly by availing yourself of all the research available. However, when you step foot into the vastness of the gold fields your best tool can be the same tool used since man’s beginning—the ability to discern information from observations. This tool helped the old timers keep food in their bellies and find gobs of gold. Much gold is still out there awaiting discovery. If you can research these old locations, make observations and learn from the old timers past work, you can find your share of the gold, too.

© ICMJ's Prospecting and Mining Journal, CMJ Inc.