How To

Free / How To

Testing Ores for Free Gold

December 2011 by Chris

I get a number of questions from people about testing and treating hard rock ores. The simplest way, but also an expensive one, is to just have an assay test done by an independent assay firm. As an alternative, one simple thing that can be done is to test an ore for its free gold content. You won’t get all the gold, only the portion that is free and easily recovered. On the other hand, in many gold ores the free gold part is the majority of the gold present in the ore. The kind of test I will be looking at in this article will tell you what sort of results that you might get if you were using a gravity-type system for treatment of hard rock ores. There are benefits to going after only the free gold component of the ore. In many places in the US, getting permits to do chemical treatment of ores using agents like cyanide is extremely difficult if not impossible.

Luckily for the miner, some higher grade ores that contain a large percentage of free gold can be treated profitably with nothing more than a finely tuned, gravity-based system. Because gravity-based systems involve no special toxic chemicals, they are normally much easier to permit. The milling systems based only on gravity  are also generally lower in cost, both to construct and operate. The downside is of course that you will miss a small percentage of the gold that can only be recovered using chemical methods. However, in areas where permitting chemicals is virtually impossible, the choice is not to recover that last percentage of gold, but is a question of whether you will be able to operate or not.

are also generally lower in cost, both to construct and operate. The downside is of course that you will miss a small percentage of the gold that can only be recovered using chemical methods. However, in areas where permitting chemicals is virtually impossible, the choice is not to recover that last percentage of gold, but is a question of whether you will be able to operate or not.

The truth is that for smaller operations in this day and age, with the political climate in places like California, non-cyanide operations are really the only viable option in many cases. I discussed the basics of this concept further in an article a few months back that addressed recovering gold without the use of cyanide. The test I am going to go through in this article is ideally suited for estimating the amount of gold you might recover by processing ores using only gravity-based systems. I think there is a significant potential market for small, profitable hard rock projects at many locations in the Western US given the very high gold prices that exist now. Making them more permittable makes them more economic.

First, we need a very accurate scale. At a minimum, we need to be able to measure at or close to thousandths of a gram—a scale that can measure 0.001 grams. Many nugget scales available from prospecting stores measure only to tenths of a gram. This is not an accuracy that would be usable for this type of test. The problem is that even rich gold ores do not contain huge amounts of gold. A typical ore may contain a quarter of an ounce of gold per ton, and we are going to process samples that weigh about 1/100th of a ton. Even if we get every bit of that quarter ounce, our resulting gold will only weigh 0.07 grams. If we use ore samples that are smaller, the resulting amount of gold we will recover will also be correspondingly smaller. So, in order to accurately weigh the gold we recover, we will need a scale with a high level of accuracy, something that can measure 0.001 grams. The accurate scale that I possess measures in hundredths of a carat, which is equal to 0.002 grams, and that is close enough.

Secondly, we will need a scale upon which we can accurately weigh the ore sample. I have a gram scale that weighs up to 1,500 grams, which is a bit over 3 pounds. We will be processing samples that weigh a lot more than that, but what I do is make multiple weighings and then add them together to get the total weight. That way, I will be able to weigh ore samples that weigh up to 20 pounds and more. We will also need a calculator to do the math of adding up weights and dividing the gold by the sample weight.

The last thing we need for this test is a way to crush the ore samples. In times past, the prospector would most commonly use some sort of mortar and pestle set up. These work perfectly well and are available at a very  reasonable cost through many prospecting supply stores, but it can take a lot of time and work to crush up a 20-pound sample in a mortar and pestle. If you crush up 20 pounds of rock this way, I guarantee your arms will be tired! Mortar and pestle type setups can be handmade if one has the welding and iron working equipment.

reasonable cost through many prospecting supply stores, but it can take a lot of time and work to crush up a 20-pound sample in a mortar and pestle. If you crush up 20 pounds of rock this way, I guarantee your arms will be tired! Mortar and pestle type setups can be handmade if one has the welding and iron working equipment.

Another option for processing larger samples is the possibility of mechanized crushing. I have a small jaw crusher, which I use to process my samples. Some equipment manufacturers make crushing systems that can be used by individual prospectors. Because I have a considerable amount of ore to work, an amount simply too large to crush in a mortar and pestle, I simply could not get by with anything less than a small, mechanized system. Even with the crusher, it still takes me hours to crush all the samples I have on hand. Either way, you need to get the rock down to the size of fine sand, with all the material being able to pass through a 1/16th-inch mesh screen. If you don’t get the rock down to size, you won’t liberate all the free gold trapped in the ore. If the gold is not set free from the enclosing rock, you will lose it, and it won’t be counted in your results.

This brings to mind the question of why one wants to process samples of more than 20 pounds. If it’s a lot of work to crush a sample, why not just use a few ounces or even maybe a couple pounds? Well, the larger amount makes the sample more accurate. Inherent in free gold sampling is the problem of the nugget affect, where a bit of ore that has significant free gold may alter the results of the sample. This would make the conclusion too high, reflecting more free gold than is actually present on average. This effect is avoided with larger sample sizes. It’s a whole lot of work to crush all that rock, but in the end, accurate results are worth the effort, especially if you are going to base a decision about buying equipment and setting up some sort of processing line.

One of the points I want to make sure to mention is that rock crushing needs to be done safely. Quartz is made of silica, and silica has a terrible effect on one’s lungs if you breathe too much of it. In all the crushing I am doing, I use a good quality dust mask with a HEPA Filter (not just one of those little white paper ones). I also wear safety glasses as it only takes one little chip to do serious damage to your eyes. Little chips are flying around all the time when you crush rock!

The last step in the process is to simply pan out the free gold from the crushed ore. You must be very careful in your panning, as you want to try your very best no to lose a single speck of gold. Very often the gold in many hard rock ores is quite fine—not always, but in a good majority of the cases, the gold is fine in size, which is why you need to be extra careful. Shake down the material more often than you normally would, and take your time in working through your material.

Before starting the process, I want to consider the fact that I have a large number of ore samples that I will be working on. I am doing this not so much because the procedure for the different types of ore is any different, but because I want you, as the reader, to see a number of different examples, and take a look at many different results. It also gives me an excuse to process a bunch of samples and get them out of my garage!

All the source mines are properties that have been known to produce free gold ores in the past. All of the samples are hand picked and represent the best looking material I saw at the mines they came from—they represent a “best case” type of scenario. If one were trying to take representative samples, it would be necessary to have a sample that is typical of the entire vein or dump that one was considering working. At this point in my writing of this article, I have not processed the samples and so I do not know what the final results will be. We will find out together and consider the repercussions.

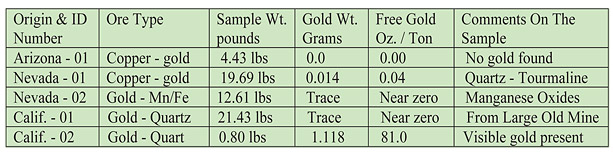

Calculation of the ounces per ton is done simply by dividing the pound weight of the sample by 2,000 (to get tons), and dividing the gram weight of the gold by 31.3 (to get troy ounces), If a purity number is available for the gold, we should multiply the ounces of gold by the purity percentage. I assumed 90% purity for my calculations. Fina lly, once you’ve completed all your calculations, to get ounces per ton we divide the number of ounces gold by the tons of sample.

lly, once you’ve completed all your calculations, to get ounces per ton we divide the number of ounces gold by the tons of sample.

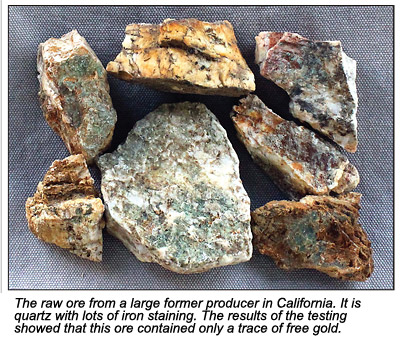

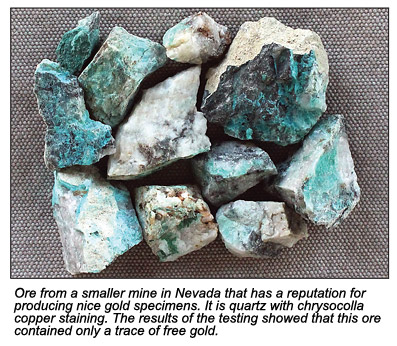

Let’s discuss the results. I was kind of surprised that so many of my samples had little or no free gold, but that is why we do testing. The data is worth having, but sometimes the data is disappointing. Arizona-01 is a prospect that has produced some really nice gold specimens, but it just goes to show that some parts of pocket mines can be rich while other parts are barren. That was a smaller sample as I brought it home on an airplane, so I couldn’t take a full 20-pound sample with me. Calif.-01 was a famous big producer, and the two Nevada mines have both produced some very rich gold ores, yet the samples produced only traces or very small amounts of gold.

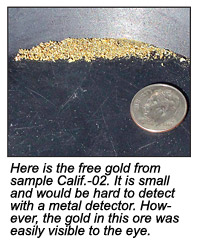

On the other hand, Calif.-02 had little bits of free gold visible on all of the pieces of ore. I only had a little bit of this material, and wish I had more. The ore was a white quartz with little iron staining or signs of pyrite. The gold was small in size and probably would be difficult to find with a detector, but it was easily visible to the eye.

So what is our conclusion? Is it worthwhile to mine and process ores like this by hand?

Certainly where little or no free gold was found, these would not be a good candidate even though all the mines I sampled were past producers of some very nice gold and some specimens. Rock that responds to a metal detector or shows visible gold would be good candidates. If I had a pickup load of rock like Calif.-02 with more than 80 ounces of gold per ton, I’d hand crush that stuff every free hour I had to spend on it!

The economics of processing hard rock ore is one of scale. If you are hand crushing in a mortar and pestle system, only very high grade materials with lots of visible gold like those that sound off on a metal detector make sense. Lower grade rock requires a larger scale of processing with only a minimum of hand work.

Would some of these ores be worthwhile if one used some sort of mechanized crushing and processing system? Perhaps a bare bones minimum hard rock plant one could build would be a small gravity-based processing system using an impact crusher and a vibrating table with the necessary feed systems. This would probably cost in the neighborhood of $15,000 to $20,000 dollars—possibly more depending on what types of system is used. Given today’s high gold prices one would only need to recover a bit more than 10 ounces to cover the equipment costs. If you had rock that ran an ounce or so per ton (or richer) you could probably make that kind of setup pay.

© ICMJ's Prospecting and Mining Journal, CMJ Inc.