All Articles

Free

Alaska's Hope-Sunrise Mining District

September 2010 by Jim

One of the major gold rushes to Alaska was to the Hope-Sunrise area on the Turnagain Arm side of the Kenai Peninsula in 1895. This area is not far from the very first discovery of gold in Alaska by the Russians in 1849, when Peter Doroshin reported a gold occurrence on the Kenai River. Doroshin searched for gold and other minerals without much apparent success for years. He followed the Kenai River to its sources and prospected the Russian River (Moffit, 1906). Doroshin missed gold-bearing ground that Americans found to be mineable half a century later. The economics of mining gold in Alaska during Doroshin’s time may not have been as lucrative as 40 to 50 years later. Whatever the reasons were for his unsuccessful prospecting, it was good for the United States because it cooled the Russians on Alaska’s mineral potential and surely was a factor in the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867.

The gold rush to the Kenai attracted prospectors from California and other goldfields in North America. They were following up on dubious rumors of Russian gold discoveries in Alaska. Gold was discovered on Cooper Creek in 1884 and on Resurrection Creek in 1888, but neither were rich enough to stir up much excitement. However, in 1894, more discoveries were made on Bear Creek and Palmer Creek, prompting the local prospectors to concentrate on the Hope area.

Many discoveries were made in the Hope-Sunrise area in 1895. The prospectors followed Sixmile Creek upstream to the most exciting strike on the peninsula at Mills Creek where 2,000 ounces were earned that summer. It was the Mills Creek discovery that launched the largest stampede to that time to the easily accessible Kenai Peninsula. The 1896 stampede to Turnagain Arm country on the northern shore of the Kenai Peninsula was described by Moffit (1906), “Several thousand men, some state the number as high as 3,000… was the banner year on Canyon Creek, 327 men being engaged in mining its gravels during the summer.” The greatest year for Kenai gold production was 1897.

After reading the fantastic reports in the nation’s newspapers of the Alaska strikes, potential stampeders must have had wistful thoughts of striking it rich in the Great Land. It was not until the news of the world famous Klondike bonanza gold strike that many could not resist their dreams any longer. Their dreams became reality and created a migration to the north. As it turned out, the 1896 Kenai stampede was a small, but exciting precursor of the Klondike rush of 1897-1898. The sensational Klondike stampede lured miners away from Kenai Peninsula leaving it almost deserted in the winter of 1897 (Barry, 1980). However, overflow from the immense Klondike stampede spawned a second stampede into the Cook Inlet region in 1898. Enough men returned to keep the region lively and productive for some years. The Klondike stampeders were disillusioned by the best ground having been already staked and the restrictive mining laws of Canada.

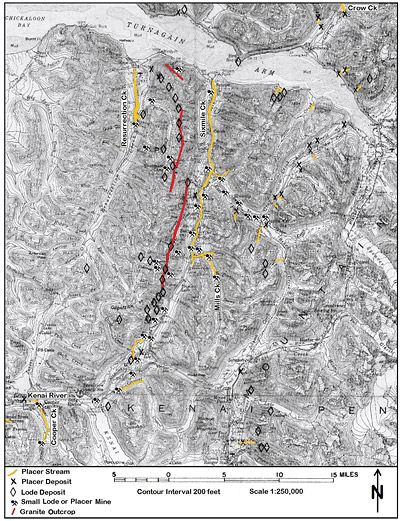

The gold in the Kenai Mountains came up with the quartz veins that intruded the slightly metamorphosed marine sedimentary rocks (phyllites, slates and greywacke). The mountains were pushed up by the Pacific Plate colliding with the Alaska portion of the North American Plate. The auriferous quartz veins were associated with granitic intrusions. These were too small to mine successfully underground for the most part, but numerous small mines and prospects attempted to prove otherwise. Most of these lodes were on divides, indicated with diamond symbols in Figure 1.

The gold in the Kenai Mountains came up with the quartz veins that intruded the slightly metamorphosed marine sedimentary rocks (phyllites, slates and greywacke). The mountains were pushed up by the Pacific Plate colliding with the Alaska portion of the North American Plate. The auriferous quartz veins were associated with granitic intrusions. These were too small to mine successfully underground for the most part, but numerous small mines and prospects attempted to prove otherwise. Most of these lodes were on divides, indicated with diamond symbols in Figure 1.

By 1900, many of the Kenai stream gravels were producing some gold, but mostly fine gold. The Kenai Mountains were well glaciated during the Ice Ages. Glaciers tend to destroy placers by bulldozing them into oblivion or burying them. Placers are found first in glaciated landscapes below areas of obvious erosion such as in and below canyons of Sixmile and Resurrection creeks. Sixmile is below Canyon and Mills creeks. Resurrection Creek is below the canyon on Palmer Creek.

Another situation for placers in glaciated landscapes, though more difficult to discover, is in buried channels also called paleo channels. Crow Creek has a good example of paleo channel. These areas will be discussed along with their mining methods.

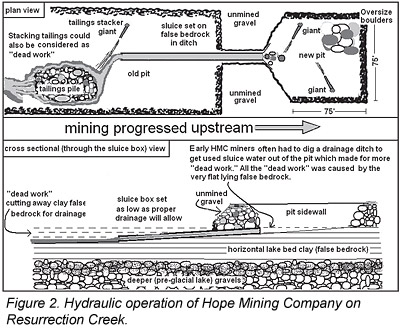

The mountainous topography and damp climate made the district conducive to hydraulic mining. Hydraulicking was widely used where it was feasible. Typically the benches were hydraulicked and the valley floor would be worked by hand unless it to could be hydraulicked too. Hope Mining Company hydraulicked Resurrection Creek gravels on the valley floor, but they had to contend with nearly flat clay that created a false bedrock. In order to accommodate the flat condition, they had to dig a ditch for the sluice and a pit for it to drain into. They also had to stack their tailings with a hydraulic giant as well as they could. Figure 2 depicts the mining method used.

Perhaps Hope Mining Company could have benefited from a rubble elevator to stack the tailings higher like was used on Cooper Creek. Today the mining method of choice at Hope Mining Company is with conventional heavy equipment.

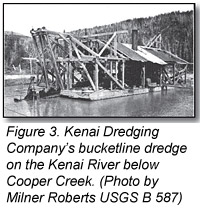

Typical stream placers were formed below less obvious canyons on tributary streams to the Kenai River. Small dredges were used on some streams, such as the Kenai River. Figure 3 shows one of these early bucketline dredges. These early dredges were unsuccessful for a variety of reasons with one being the abundance of large “bowlders” (as they spelled boulders back then) that the glaciers left behind and the dredges could not handle.

Kenai Dredging Company’s property was on a gravel bar about a mile below the mouth of Cooper Creek’s small canyon. It’s said to have yielded (Johnson, 1915) “$167 in gold from 9½ cubic yards…” (0.72 ounces per cubic yard from a gravel bar) “…and from 2 to 25 cents from each pan from the river bars.” These numbers sound like some serious high-grading was occurring for promotional purposes, no doubt.

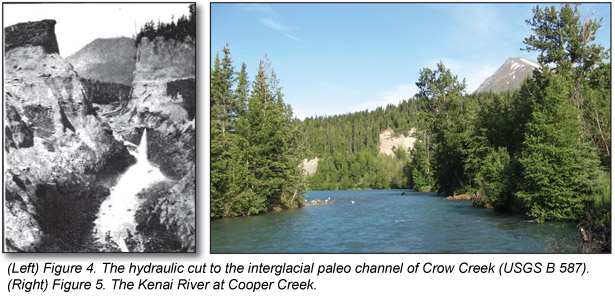

Not quite on the Kenai Peninsula, but similar to it geologically, is the famous Crow Creek Mine across Turnagain Arm. This mine worked typical stream gravels and a paleo channel that was buried 40 to 50 feet deep under a bench. This area was well glaciated during the Ice Ages. The Crow Creek placers formed both before the glaciers and after they receded. Crow Creek is both a present stream placer and a pre-glacial (paleo) stream channel placer. Often the paleo placers are richer and only managed to survive the glacier’s erosive attack by being protected somehow. In this case the paleo channel was protected by being incised deep into bedrock. Figure 4 is an historic photo of the hydraulically washed out cut that followed the old channel.

Over 100 years of placer mining on the Kenai Peninsula has produced about 133,800 ounces of gold. Hard rock mines produced an additional 30,000 ounces. Suction dredging is currently the dominate mining method.

Thinking about journeying to Alaska for a summer of mining on the Kenai Peninsula? Of course, there are privately-owned mining claims, but it is possible to steer around them. The Chugach National Forest and Bureau of Land Management has helped out in this matter. They put together a gold mining website on the National Forest portion of the Kenai Peninsula that can be found at www.alaskaoutdoorjournal.com/Activities/Goldpanning/kpgold.html. It is worthwhile for finding the spots open and available for mining. Suction dredges and highbankers have been more useful than nugget detecting because the gold particles tend to be too small for most detectors. Suction dredges (4-inch or smaller) are permitted from May 15 to July 15 in designated areas on Sixmile and Resurrection creeks. A permit from ADF&G is required for dredging.

Mining is also available for a fee the Crow Creek Mine. More information is available on the Internet at www.crowcreekmine.com

- Barry, M.J., 1980, Kenai Peninsula Mining Highlights: Hope, Sunrise, and Lower Cook Inlet, in Mining in Alaska’s Past; Office of History and Archeology, Alaska Department of Natural Resources, Anchorage.

- Martin, G.C., Johnson, B.L., and Grant, 1915, Geology and Mineral Resources of Kenai Peninsula, Alaska: US Geological Survey Bulletin 587.

- Moffit, F.H., 1906, Mineral Resources of Kenai Peninsula, Alaska: US Geological Survey Bulletin 277.

- Paige, Sidney and Knopf, Adoph, 1907, Reconnaissance in the Matanuska and Talkeetna Basins, with notes on the placers of adjacent regions: US Geological Survey Bulletin 314.

-

Tuck, Ralph, 1933, The Moose Pass-Hope district, Kenai Peninsula, Alaska: US Geological Survey Bulletin 849-I.

© ICMJ's Prospecting and Mining Journal, CMJ Inc.